Contracts

Agreements between two entities, creating an enforceable obligation to do, or to refrain from doing, a particular thing.

Nature and Contractual Obligation

The purpose of a contract is to establish the agreement that the parties have made and to fix their rights and duties in accordance with that agreement. The courts must enforce a valid contract as it is made, unless there are grounds that bar its enforcement.

Terms of Contracts

Terms of a contract are the points agreed upon by both the parties to the contract. One who has made an offer and the other who has accepted the offer and the proposal of the first party.

Enforcement of Contracts

The courts may not create a contract for the parties. When the parties have no express or implied agreement on the essential terms of a contract, there is no contract. Courts are only empowered to enforce contracts, not to write them, for the parties. A contract, in order to be enforceable, must be a valid. The function of the court is to enforce agreements only if they exist and not to create them through the imposition of such terms as the court considers reasonable.

A contract is formed between competent parties for lawful objectives. Contracts by competent persons, equitably made, are valid and enforceable. Parties to a contract are bound by the terms to which they have agreed if it is not made by Fraud, duress, or Undue Influence.

The binding force of a contract is based on the fact that it is based on the agreed and consented terms in Good Faith. A contract, once formed, does not contemplate a right of a party to reject it. Contracts that were mutually entered into between parties with the capacity to contract are binding obligations and may not be set aside due to the caprice of one party or the other unless a statute provides to the contrary.

Types of Contracts

Contracts under Seal Traditionally, a contract was an enforceable legal document only if it was stamped with a seal. The seal represented that the parties intended the agreement to entail legal consequences. Seal was a symbol of the solemn acceptance of the legal effect and consequences of the agreement. In the past, all contracts were required to be under seal in order to be valid, but the seal has lost some or all of its effect by statute in many countries. The seal worth also reduced by the fact that the courts started recognizing the implied contracts.

Express Contracts In an express contract, the parties state the terms, either orally or in writing, at the time of its formation. There is a definite written or oral offer that is accepted by the offeree (i.e., the person to whom the offer is made) in a manner that explicitly demonstrates consent to its terms.

Implied Contracts These are mutual agreement and intent to promise which have not been expressed in words. The term quasi-contract is a more accurate designation of contracts implied in law. Implied contracts are as binding as express contracts. An implied contract depends on substance for its existence; therefore, for an implied contract to arise, there must be some act or conduct of a party, in order for them to be bound.

Executed and Executory Contracts An executed contract is one in which nothing remains to be done by either party. An executory contract is one in which some future act or obligation remains to be performed according to its terms.

Bilateral and Unilateral Contracts The exchange of mutual, reciprocal promises between two parties is a Bilateral Contract. A bilateral contract is sometimes called a two-sided contract because of the two promises that constitute it.

A unilateral contract involves a promise that is made by only one party. The offeror promises to do a certain thing if the offeree performs a requested act. The performance constitutes an acceptance of the offer, and the contract then becomes executed. Acceptance of the offer may be revoked, however, until the performance has been completed.

Unconscionable Contracts An unconscionable contract is one that no mentally competent person would accept and that no fair and honest person would enter into. Courts find that unconscionable contracts usually result from the exploitation of consumers who are poorly educated, impoverished, and unable to understand.

Adhesion Contracts: Adhesion contracts are those that are drafted by the party who has the greater bargaining advantage, providing the weaker party with only the opportunity to adhere to or to accept the contract or to reject it. These types of contract are often described by the saying “Take it or leave it.” Not all adhesion contracts are unconscionable, as the terms of such contracts do not necessarily exploit the party who assents to the contract. Courts, however, often refuse to enforce contracts of adhesion on the grounds that a true meeting of the minds never existed, or that there was no acceptance of the offer because the purchaser actually had no choice in the bargain.

Aleatory Contracts: In this type of contract, one or both parties assume risk. A fire insurance policy is a form of aleatory contract, as an insured will not receive the proceeds of the policy unless a fire occurs, an event that is uncertain to occur.

Void and Voidable Contracts Contracts can be either void or Voidable. A void contract imposes no legal rights or obligations upon the parties and is not enforceable by a court. It is, in effect, no contract at all.

A voidable contract is a legally enforceable agreement, but it may be treated as never having been binding on a party who was suffering from some legal disability or who was a victim of fraud at the time of its execution. The contract is not void unless or until the party chooses to treat it as such by opposing its enforcement. A voidable contract may be ratified either expressly or impliedly by the party who has the right to avoid it. An express ratification occurs when that party who has become legally competent to act declares that he or she accepts the terms and obligations of the contract. An implied ratification occurs when the party, by his or her conduct, manifests an intent to ratify a contract, such as by performing according to its terms. Ratification of a contract entails the same elements as formation of a new contract. There must be intent and complete knowledge of all material facts and circumstances.

Which Law Governs

Although a general body of contract law exists, some aspects of it, such as construction vary among the different jurisdictions. When courts must select the law to be applied with respect to a contract, they consider what the parties intended as to which law should govern; the place where the contract was entered into; and the place of performance of the contract. Courts generally apply the law that the parties expressly or impliedly intend to govern the contract, provided that it bears a reasonable relation to the transaction and the parties acted in good faith. Some jurisdictions follow the law of the place where the contract was performed, unless the intent of the parties is to the contrary. Where foreign law governs, contracts may be recognized and enforced under the doctrine of comity i.e., the acknowledgment that one nation gives within its territory to the legislative, executive, or judicial acts of another nation.

Elements of a Contract

The requisites for formation of a legal contract are an offer, an acceptance, competent parties who have the legal capacity to contract, lawful subject matter, mutuality of agreement, consideration, mutuality of obligation, and, if required under the Statute of Frauds, a writing.

Offer: An offer is a promise that is, by its terms, conditional upon an act, forbearance, or return promise being given in exchange for the promise or its performance. Any offer must consist of a statement of present intent to enter a contract; a definite proposal that is certain in its terms; and communication of the offer to the identified, prospective offeree. If any of these elements are missing, there is no offer to form the basis of a contract.

Preliminary negotiations, advertisements, invitations to bid Preliminary negotiations are clearly distinguished from offers because they contain no demonstration of present intent to form contractual relations. No contract is formed when prospective purchasers respond to such terms, as they are merely invitations or requests for an offer. An advertisement, price quotation, or catalogue is customarily viewed as only an invitation to a customer to make an offer and not as an offer itself. In addition, the courts have held that an advertisement is an offer for a unilateral contract that can be revoked at the will of the offeror, the business enterprise, prior to performance of its terms.

An exception exists, however, to the general rule on advertisements. When the quantity offered for sale is specified and contains words of promise, such as “first come, first served,” courts enforce the contract where the store refuses to sell the product when the price is tendered. Where the offer is clear, definite, and explicit, and no matters remain open for negotiation, acceptance of it completes the contract. New conditions may not be imposed on the offer after it has been accepted by the performance of its terms.

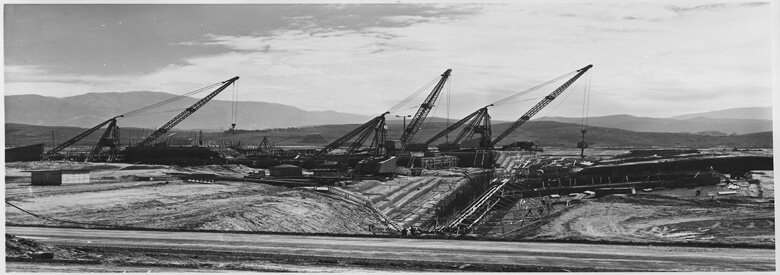

An advertisement or request for bids for the sale of particular property or the erection or construction of a particular structure is merely an invitation for offers that cannot be accepted by any particular bid. A submitted bid is, however, an offer, which upon acceptance by the offeree becomes a valid contract.

Termination of an offer An offer remains open until the expiration of its specified time period or, if there is no time limit, until a reasonable time has elapsed. A reasonable time is determined according to what a reasonable person would consider sufficient time to accept the offer.

The death or insanity of either party, before an acceptance is communicated, causes an offer to expire. If the offer has been accepted, the contract is binding, even if one of the parties dies thereafter. The destruction of the subject matter of the contract; conditions that render the contract impossible to perform; or the supervening illegality of the proposed contract results in the termination of the offer.

When the offeror, either verbally or by conduct, clearly demonstrates that the offer is no longer open, the offer is considered revoked when learned by the offeree. Where an offer is made to the general public, it can be revoked by furnishing public notice of its termination in the same way in which the offer was publicized.

Irrevocable offers Offer for a unilateral contract becomes irrevocable as soon as the offeree starts to perform the requested act, because that action serves as consideration to prevent revocation of the offer. Some courts hold that an offer for a unilateral contract may be revoked at any time prior to completion of the act bargained for, even after the offeree has partially performed it.

Acceptance Acceptance of an offer is an expression of assent to its terms. It must be made by the offeree in a manner requested or authorized by the offeror. An acceptance is valid only if the offeree knows of the offer; the offeree manifests an intention to accept; the acceptance is unequivocal and unconditional; and the acceptance is manifested according to the terms of the offer.

In bilateral contracts, the offer is effective when the offeree receives it. The offeree may accept it until the offeree receives notice of revocation from the offeror. Thereafter, an offer is revoked. In contracts that do not involve the sale of goods, acceptance must comply exactly with the requirements of the offer and must omit nothing from the promise or performance requested.

Unsolicited goods at Common Law, the recipient of unsolicited goods in the mail was not required to accept or to return them, but if the goods were used, a contract and a concomitant obligation to pay for them were created. The recipient may use the goods and is under no duty to return or pay for them unless he or she knows that they were sent by mistake.

Agreements to agree An “agreement to agree” is not a contract. This type of agreement is frequently employed in industries that require long-term contracts in order to ensure a constant source of supplies and outlet of production. Mutual manifestations of assent that are, in themselves, sufficient to form a binding contract are not deprived of operative effect by the mere fact that the parties agree to prepare a written reproduction of their agreement.

Competent Parties A natural person who agrees to a transaction has complete legal capacity to become liable for duties under the contract unless he or she is an infant, insane, or intoxicated.

Infants An infant is defined as a person under the age of 18 or 21, depending on the particular jurisdiction. A contract made by an infant is voidable but is valid and enforceable until or unless he or she disaffirms it.

Mental incapacity When a party does not comprehend the nature and consequences of the contract when it is formed, he or she is regarded as having mental incapacity. A contract made by such a person is void and without any legal effect. Neither party may be legally compelled to perform or comply with the terms of the contract.

Intoxicated persons A contract made by an intoxicated person is voidable. When a person is inebriated at the time of entering into a contract with another and subsequently becomes sober and either promises to perform the contract or fails to disaffirm it within a reasonable time after becoming sober, then that person has ratified his or her voidable contract and is legally bound to perform.

Subject Matter Any undertaking may be the subject of a contract, provided that it is not proscribed by law. Contracts that provide for the commission of a crime or any illegal objective are also void.

Future rights and liabilities A person may not legally contract concerning a right that he or she does not have. A seller of a home who does not possess clear title to the property may not promise to convey it without encumbrances.

Mutual Agreement There must be an agreement between the parties, or mutual assent, for a contract to be formed. In order for an agreement to exist, the parties must have a common intention or a meeting of minds on the terms of the contract and must subscribe to the same bargain.

Consideration A valid contract requires some exchange of consideration. As a general rule, in a bilateral contract, one promise is valid consideration for the other. In a unilateral contract, the agreed performance by the offeree furnishes the necessary consideration and also operates as an acceptance of the offer.

Mutuality of Obligation Where promises constitute the consideration in a bilateral contract, they must be mutually binding. This concept is known as mutuality of obligation.

Past consideration consists of actions that occurred prior to the making of the contractual promise, without any purpose of inducing a promise in exchange. It is not valid, because it is not furnished as the bargained-for exchange of the present promise.

Statute of Frauds The statute of frauds was enacted by the English Parliament in 1677 and has since been the law in both England and in the United States in varying forms. It requires that certain types of contracts be in writing. The purpose of the statute is to prevent the proof of a nonexistent agreement through fraud or perjury in actions for breach of an alleged contract.

Reality of Consent The parties must mutually assent to the proposed objectives and terms of a contract in order for it to be enforceable. The manifestation of the common intent of the parties is discerned from their conduct or verbal exchanges. What one party secretly intended is irrelevant if his or her conduct appears to demonstrate agreement. There will be no binding contract without the real consent of the parties. Apparent consent may be vitiated because of mistake, fraud, innocent misrepresentation, duress, or undue influence, all of which are defenses to the enforcement of the contract.

Mutual Mistake If the mutual mistake significantly changed the subject matter of the contract, a court will refuse to enforce the contract. If, however, the difference in the subject matter of the contract concerned some incidental.

Unilateral Mistake Ordinarily, a unilateral mistake affords no basis for avoiding a contract, but a contract that contains a typographical error may be corrected.

Mistake of Law When a party who has full knowledge of the facts reaches an erroneous conclusion as to their legal effect, such a mis-take of law will not invalidate a contract or affect its enforceability.

Illiteracy Illiteracy neither excuses a party from the duty of learning the contents of a written contract nor prevents the mutual agreement of the parties. An illiterate person is capable of giving real consent to a contract; the person has a duty to ask someone to read the contract to him or her and to explain it, if necessary.

Fraud Fraud prevents mutual agreement to a contract because one party intentionally deceives another as to the nature and the consequences of a contract. It is the willful misrepresentation or concealment of a material fact of a contract, and it is designed to persuade another to enter into that contract. A contract that is based on fraud is void or voidable, because fraud prevents a meeting of the minds of the parties.

Misrepresentation without Fraud A contract may be invalidated if it was based on any innocent misrepresentation pertaining to a material matter on which one party justifiably relied.

Duress Duress is a wrongful act or threat by one party that compels another party to perform some act, such as the signing of a contract, which he or she would not have done voluntarily. As a result, there is no true meeting of minds of the parties and, therefore, there is no legally enforceable contract. Blackmail, threats of physical violence, or threats to institute legal proceedings in an abusive manner can constitute duress. A contract that is induced by duress is either void or voidable.

Undue Influence Undue influence is unlawful control exercised by one person over another in order to substitute the first person’s will for that of the other. It generally occurs in two types of situations. In the first, a person takes advantage of the psychological weakness of another, in order to influence that person to agree to a contract to which, under normal circumstances, he or she would not otherwise consent. The second situation entails undue influence based on a fiduciary relationship that exists between the parties. This occurs where one party occupies a position of trust and confidence in relation to the other, as in familial or professional-client relationships. The question of whether the assent of each party to the contract is real or induced by factors that inhibit the exercise of free choice determines the existence of undue influence. Mere legitimate persuasion and suggestion that do not destroy free will are not considered undue influence and have no effect on the legality of a contract.

Assignments

An assignment of a contract is the transfer to another person of the rights of performance under it. Contracts were not assignable at early common law, but today most contracts are assignable unless the nature of the contract or its provisions demonstrates that the parties intend to make it personal to them and therefore incapable of assignment to others.

Joint and Several Contracts

Joint and several contracts always entail multiple promises for the same performance. Two or more parties to a contract who promise to the same promisee that they will give the same performance are regarded as binding themselves jointly, severally, or jointly and severally.

Joint liability ensues only when promisors make one promise as a unit. The party may enforce the contract only against one promisor or against any number of joint promisors.

Third-Party Beneficiaries

There are only two principal parties, the offeror and the offeree, to an ordinary contract. The terms of the contract bind one or both parties.. The effect of a third-party contract is to provide, to a party who has not assented to it, a legal right to enforce the contract.

Conditions and Promises of Performance

The duty of performance under many contracts is contingent upon the occurrence of a designated condition or promise. A condition is an act or event, other than a lapse of time, that affects a duty to render a promised performance that is specified in a contract.

Types of Conditions Conditions precedent, conditions concurrent, and conditions subsequent are types of conditions that are commonly found in contracts. A condition precedent is an event that must exist as a fact before the promisor incurs any liability pursuant to it. A condition concurrent must exist as a fact when both parties to a contract are to perform simultaneously. A condition subsequent is one that, when it exists, ends the duty of performance or payment under the contract.

Substantial Performance Courts determine whether there has been a breach or a substantial performance of a contract by evaluating the purpose to be served; the excuse for deviation from the letter of the contract; and the cruelty of enforced adherence to the contract.

Satisfactory Performance To check and determine performance was satisfactory the test is what would satisfy a reasonable person.

Divisible Contracts A contract is divisible when the performance of each party is divided into two or more parts; each party owes the other a corresponding number of performances; and the performance of each part by one party is the agreed exchange for a corresponding part by the other party. If it is divisible, the contract, for certain purposes, is treated as though it were a number of contracts, as in employment contracts and leases.

Discharge of Contracts

The duties under a contract are discharged when there is a legally binding termination of such duty by a Voluntary Act of the parties or by operation of law. The two most significant methods of voluntary discharge are Accord and Satisfaction and novation. An accord is an agreement to accept some performance other than that which was previously owed under a prior contract. Satisfaction is the performance of the terms of that accord. Both elements must occur in order for there to be discharge by these means. A novation involves the substitution of a new party while discharging one of the original parties to a contract by agreement of all three parties. A new contract is created with the same terms as the original one, but the parties are different. Contractual liability may be voluntarily discharged by the agreement of the parties, by estoppel, and by the cancellation, intentional destruction, or surrender of a contract under seal with intent to discharge the duty. The discharge of a contractual duty may also occur by operation of law through illegality, merger, statutory release, such as a discharge in bankruptcy, and objective impossibility. Merger takes place when one contract is extinguished because it is absorbed into another.

Breach of Contract

An unjustifiable failure to perform all or some part of a contractual duty constitutes a breach of contract. It ensues when a party who has a duty of immediate performance fails to perform, or when one party hinders or prevents the performance of the other party.

Remedies

Damages, reformation, Rescission, restitution, and Specific Performance are the basic remedies available for breach of contract.

Types of Contract:

types are grouped into categories:

- Fixed-price contracts

- Cost-reimbursement contracts

- Incentive Contracts

- Indefinite – Delivery Contracts

- Time – And-Materials Contracts

- Labor – Hour Contracts

- Sealed Bidding

- Negotiation

- Fixed – Price Contracts

Types of contracts can include:

- Written contracts

- Verbal contracts

- Standard form contracts

- Period contracts

- Written contracts

Benefits of a written contract

A written contract can:

- Provide proof of what was agreed between you and the hirer

- Help to prevent misunderstandings or disputes by making the agreement clear from the outset

- Give you security and peace of mind by knowing you have work, for how long and what you will be paid

- Clarify your status as an independent contractor by stating that the contract is a ‘services contract’ and not an ’employment contract’. This will not override a ‘sham’ contract, but a court will take the statement into account if there is any uncertainty about the nature of the relationship reduce the risk of a dispute by detailing payments, timeframes and work to be performed under the contract

- Set out how a dispute over payments or performance will be resolved

- Set out how the contract can be varied

- Serve as a record of what was agreed

- Specify how either party can end the contract before the work is completed.

- Risks of not having a written contract

When a contract is not in writing, you are exposing yourself and your business to a number of risks:

- The risk that you or the hirer misunderstood an important part of the agreement, such as how much was to be paid for the job or what work was to be carried out

- The risk that you will have a dispute with the hirer over what was agreed because you are both relying on memory

- The risk that a court won’t enforce the contract because you may not be able to prove the existence of the contract or its terms.

When a written contract is essential

It is always better to have your contract in writing, no matter how small the job is. Any contract with a hirer that involves a significant risk to your business should always be carefully considered and put in writing. This is advisable even if it means delaying the start of the work. A written contract is essential:

- When the contract price is large enough to make or break your business if you don’t get paid

- Where there are quality requirements, specifications or specific materials that must be used

- Where there is some doubt that the hirer has enough money to pay you

- When you must have certain types of insurance for the type of work you are doing

- Where the contract contains essential terms, such as a critical date for the completion of the work before payment can be made

- Where you or the hirer need to keep certain information confidential

- When it is required by your insurance company for professional indemnity purposes

- Where there is a legal obligation to have a written contract (eg. trade contracts for building work in Queensland).

Verbal contracts

Many independent contracting arrangements use verbal contracts, which only work well if there are no disputes. A handshake agreement may still be a contract and may (though often with difficulty) be enforced by a court. However, verbal contracts can lead to uncertainty about each party’s rights and obligations. A dispute may arise if you have nothing in writing explaining what you both agreed to do.

Part verbal, part written contracts

Some agreements may be only partly verbal. For example, there may be supporting paperwork such as a quote or a list of specifications that also forms part of the contract. At the very least, you should write down the main points that you agreed with the hirer to avoid relying on memory. Keep any paperwork associated with the contract. The paperwork can later be used in discussions with the hirer to try to resolve a problem. If the dispute becomes serious, it may be used as evidence in court.

The most important thing is that each party clearly understands what work will be done, when it will be completed and how much will be paid for the work.

Examples of paperwork that may support a verbal contract

- E-mails

- Quotes with relevant details

- Lists of specifications and materials

- Notes about your discussion—for example, the basics of your contract written on the back of an envelope (whether signed by both of you or not).

If the contract is only partly written or the terms of the work are set out in a number of separate documents (e-mail, quote etc.), it is to your benefit to make sure that any formal agreement you are being asked to sign refers to or incorporates those documents. At the very least, make sure the contract does not contain a term to the effect that the formal document is the ‘entire agreement’.

Standard form contracts

A ‘standard form’ contract is a pre-prepared contract where most of the terms are set in advance and little or no negotiation between the parties occurs. Often, these are printed with only a few blank spaces for filling in information such as names, dates and signatures.

Period contracts

Period contracts can work well for both parties. They allow for the flexibility of performing intermittent work over an agreed period.